How Louis Braille Impacted My Life

Jan 04, 2021It's my good fortune to have Tiffany J. Kim as a writing student (on another website), and she's also enrolled in courses here at Lucky Learning. When I learned that Tiff had a desire to honor Louis Braille on his birthday, I asked her to write for this blog. Please welcome Tiffany! I know you'll appreciate all the heart and personal experience she put into writing this. — Milli

Guest post by Tiffany J. Kim

IF YOU HAD BEEN BORN BLIND before the late nineteenth century, your fate would have been sealed. The chances were high that you would end up having to beg on the streets for coins and pray that the compassion of your fellow townspeople would help you secure a piece of bread. If you were fortunate enough to be gifted with musical talent, then you might be able to earn your coins by singing or playing

an instrument. Still, the story was the same. If you were blind, there were very few possibilities, and those availed to you were grim.

This bleak outlook was all changed by one man by the name of Louis Braille, who invented the system of reading and writing still used by the blind today.

Louis Braille was born on January 4, 1809 in the little country village of Coupvray, Seine-et-Marne, France. He was the fourth child of Mr. and Mrs. Simon-René Braille, and his father was a skilled harness maker. At the age of three, while playing with his father’s tools, Louis pierced his right eye with an awl as he tried to drive it through a piece of scrap leather.

The wound became infected and this infection spread to his other eye, leading to complete blindness by the age of five. Fortunately for Louis, his parents were quite progressive and insisted that he be provided with educational and vocational training. As such, he was sent to the Royal Institute for the Blind in Paris, one of the first schools in the world established to educate the blind.

Prior to the invention of Braille in 1824, the system used by the blind consisted of raised letters embossed on wet paper with copper wiring. These raised letters had to be felt one by one and, since they were quite large, the process of reading was laborious and time-consuming. Books produced in this way were bulky, delicate, and contained limited information, since transcribing a book’s entire contents would require far too much space. More troubling, however, was the fact that writing for the blind was impossible.

In 1821, Mr. Braille heard about a system of writing known as Night Writing, developed by Captain Charles Barbier. Consisting of combinations of twelve dots as well as dashes, it was far too complex for soldiers to learn. Louis drew inspiration from this system, simplified the code to consist of six dots—arranged in the same fashion as the six you see whenever you play dice—and created the first iteration of his code in 1824.

Ironically, Mr. Braille used an awl and pieces of leather to work on his code, so the same tool that blinded him ended up opening a doorway to literacy and communication.

Mr. Braille went on to work as a teacher at the Royal Institute for the Blind. He was also an accomplished musician who played both the cello and the organ. As such, he also created the Music Braille Code and designed it in such a way that it could be used by any musician, regardless of which instrument was being played.

In France in 1854, Louis Braille's system was posthumously adopted as the official way for the blind to read and write. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that it was used universally throughout the world, and adapted into over 85 different codes to accommodate the world’s many different languages.

In 1985, as a result of optic nerve hypoplasia, I myself was born completely blind. From an early age, reading books was my passion. Whenever I went to my school’s resource room for the blind, the first thing I would do was head to their library of Braille books and get lost among the shelves, looking for something I had not yet read.

I also remember long nights reading books under the covers. When my parents came to check on me, I’d pretend to be asleep. In truth, I would often be waiting, with bated breath, wondering if they would be fooled into thinking I had gone to sleep so they would turn off the light and let me get back to whatever fantastical world I had gotten sucked into.

As a child, I was also an avid writer. There were many days when I would use my Perkins Brailler (a typewriter for the blind) to create my stories and poems, and I went through many boxes of Braille paper. Because it was significantly more expensive to acquire, I ended up just using regular copy paper because my folks couldn’t keep up with how much I used.

One of my favorite things to do was to play school, so I would create assignments for myself. Sometimes they were random math problems, but at other times I’d pretend to be a witch needing to study potion recipes.

I even used my Brailler to learn how to draw using the Braille code, and I still know how to draw a lucky shamrock.

Braille has opened up a world of possibilities for me, and I’m honestly not sure where I'd be without it. Braille allowed me to win the spelling bee at my junior high. I remember being given reams of paper that contained many words from different categories, some of which—such as flibbertigibbet, martinet, and lachrymose—I still remember to this day.

Braille also enabled me to excel in science and math. In fact, had I had just a bit more faith in myself when I was younger, I’m sure I would have worked harder and tried to tackle medical school so I could pursue a dream I had to become a pediatrician.

Nowadays, my primary use of Braille is pleasure reading. My husband enjoys hearing me read aloud. It’s a lot of fun because I love getting into character and immersing us both into the world of stories. He also thinks my voice is soothing so tends to fall asleep quite readily when we lie together and I turn on my Braille notetaker. The books I used to read, under the covers, can now all be loaded onto a USB stick and read on a Braille display. The dots are created by pins that pop up and retract to form the words in these electronic books, much the way printed words change on an EReader’s display.

It saddens me to know that a lot of teachers these days think Braille is too difficult to teach and believe their students can get by using a screen reader and dictation alone. I have heard that only about 10% of blind individuals are able to read and write in Braille. I listened to audiobooks, too, and I know they've experienced a resurgence in the world at large—but when you listen to a book, it doesn’t teach you how to create your own words. For me, whose lifeblood is writing, not being able to form my own words, sentences, and stories would be torture.

I think the most significant thing I did with Braille was write up, then read out, my wedding vows when I got married this past August. On a special day like this, where the tears were flowing, I’m sure that relying upon my memory would have resulted in quite a few bloopers!

I’m grateful for the gift that Mr. Louis Braille gave to me, and the world as a whole, when he provided us with the keys to a world of possibility: communication, literacy, independence, and empowerment. I am blessed to be able to write, create, dream, and count on a future in which I do not have to stand on a street corner begging and hoping that the kindness of a stranger will allow me to eat for one more day.

-----

TIFFANY J. KIM was born clutching a pen in her hand and has been writing from the day she came out into the world in a sleepy little town known as Oxnard, California. When she's not writing rhyming poems or stories guaranteed to make you laugh, she enjoys baking sweet and tasty treats, such as snickerdoodles and lemon bars; singing karaoke; reading culinary cozy mysteries; and listening to music in the Irish, modern country, reggae, doo-wop, and classic soul genres. Tiffany earned her Masters degree in rehabilitation counseling from California State University and currently works in her chosen field. She is happily married to a musician named Beau Wilding, and they live in the California beach community of Carpinteria.

-----

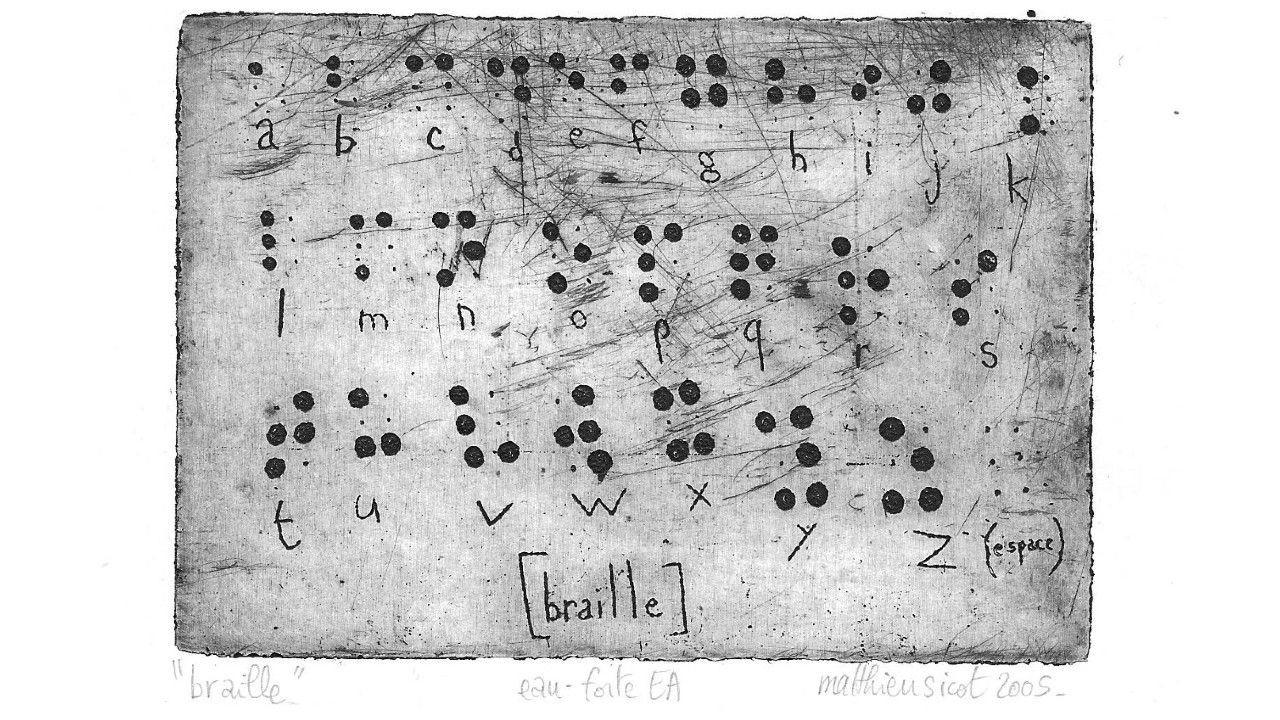

Etching of Braille dots by Matthieu Sicot from Wikimedia Commons. Used with permission.